LLMs overview

Chatting with a GPT

If you’ve used ChatGPT or Claude to summarise some difficult text (legalese perhaps) or answer a question for you, then you’ve seen how impressive these AIs can be. They appear to know everything, and can modulate their answers stylistically and cater to your thinking in a thousand ways. But they’re so mystical! An absolute black box of magic. I hope to, in this post, unpack what a Large Language Model (LLM) is and broadly how it works.

What is an LLM

Large Language Models, or LLMs, as their name suggests, deal with language. They have an internal model of natural language, based on their training. This internal model captures multiple levels of meaning, from individual words to word-group interactions, facts, syntax, semantics. An internal vocabulary is built up, using the given training data - eg. “all of wikipedia, in english”. From this vocabulary, which represents all the words and concepts the model can operate on, the model learns connections between the items and how to use them to construct coherent language as output. For example, if one were to train a Language Model only on Shakespearean English, the LLM’s vocabulary and internal concepts would reflect this.

An example of an LLM is a GPT - a Generative Pretrained Transformer. These can be used for language translation or querying. Consider the task of French to English. The GPT is trained on translation data such that it builds up an internal model of how the French language corresponds to English, including all manner of nuance, idioms, etc (dependeng on the data used). Then, when given a sentence in French as input, the internal model can operate on this sentence and provide the english translation.

LLMs typically are tasked with natural language-based tasks. They can complete partial sentences: “Einstein was a theoretical __” (what comes next?). They can fill in a middle blank: “The best racer ever was __ and they often won by a huge margin” (what goes there?). Such skills can be used in question-answering or fact-checking.

They can extract information, like named entities: “Einstein worked in the Swiss patent office in Zurich” (what are the names there? Einstein, Swiss, Zurich). They can summarise and evaluate text, like give sentiment analysis (was this paragraph positive?). They can even answer questions, and the most well known LLM to do this is good ole ChatGPT.

How do LLMs work?

It might appear that LLMs do proper human-like thinking behind the scenes. In a way, that’s true - they reason about relationships between words and deeper semantic meaning. You perform similar mental tasks, however subconcious, when reading text like this, for example. But it only appears this way because we have managed to approximate this process with a few mathematical concepts and operations.

All these models - GPTs, Llamas, BERTs, etc - at their core, LLMs combine two ideas: “embedding space”, that maps tokens to numbers, and Transformers (the process that crunches those numbers). Transformers will make more sense in the context of the embedding space, so let’s start there.

Embedding Space

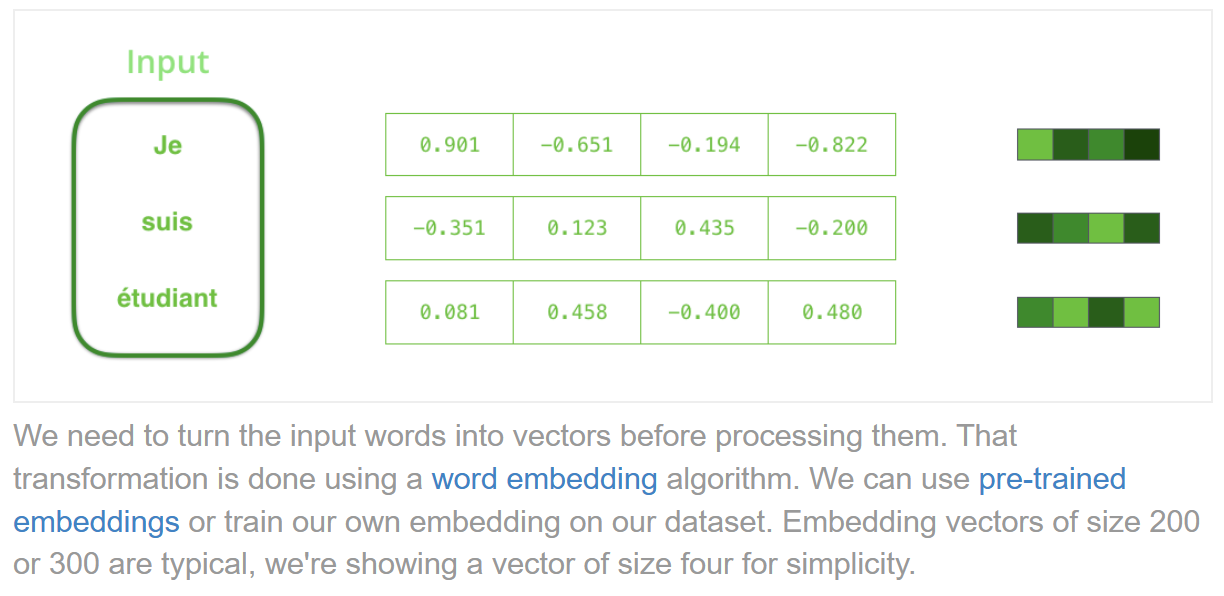

These language models work on words: either as input, or as output. We pass in “generate a poem about cats”, or get out a summary of a wikipedia page. Do they operate on words internally? No. They operate on numbers. So how do we get from words to numbers?

One way would be to assign every word in the dictionary a number:

- ‘a’ - 1

- ‘and’ - 2

- ‘aardvark’ - 3

and so on.

But if ‘angle’ = 53 and ‘blueberry’ = 286, adding them is meaningless unless our numbering encodes semantic relationships. We need the composition of these numbers associated with words to make sense. So what we do is we have a vector space for these numbers. Think of a 3-dimensional vector space to represent positions in a room: (x, y, z). Each dimension means something different. The amount of forwards, the amount of sideways, the amount of up. These are all directions in a room though. We can get more abstract. If you want to classify people, you might use a vector: a dimension for lightness or darkness of skin colour, a dimension for height, a dimension for weight, a dimension for eye colour, a dimension for … foot size, and so on. These dimensions need not be unique too. We can have some that correlate: finger length and palm area are strongly correlated, but there’s no stoppping us from writing both down We could have, say, 200 measurements to describe a person.

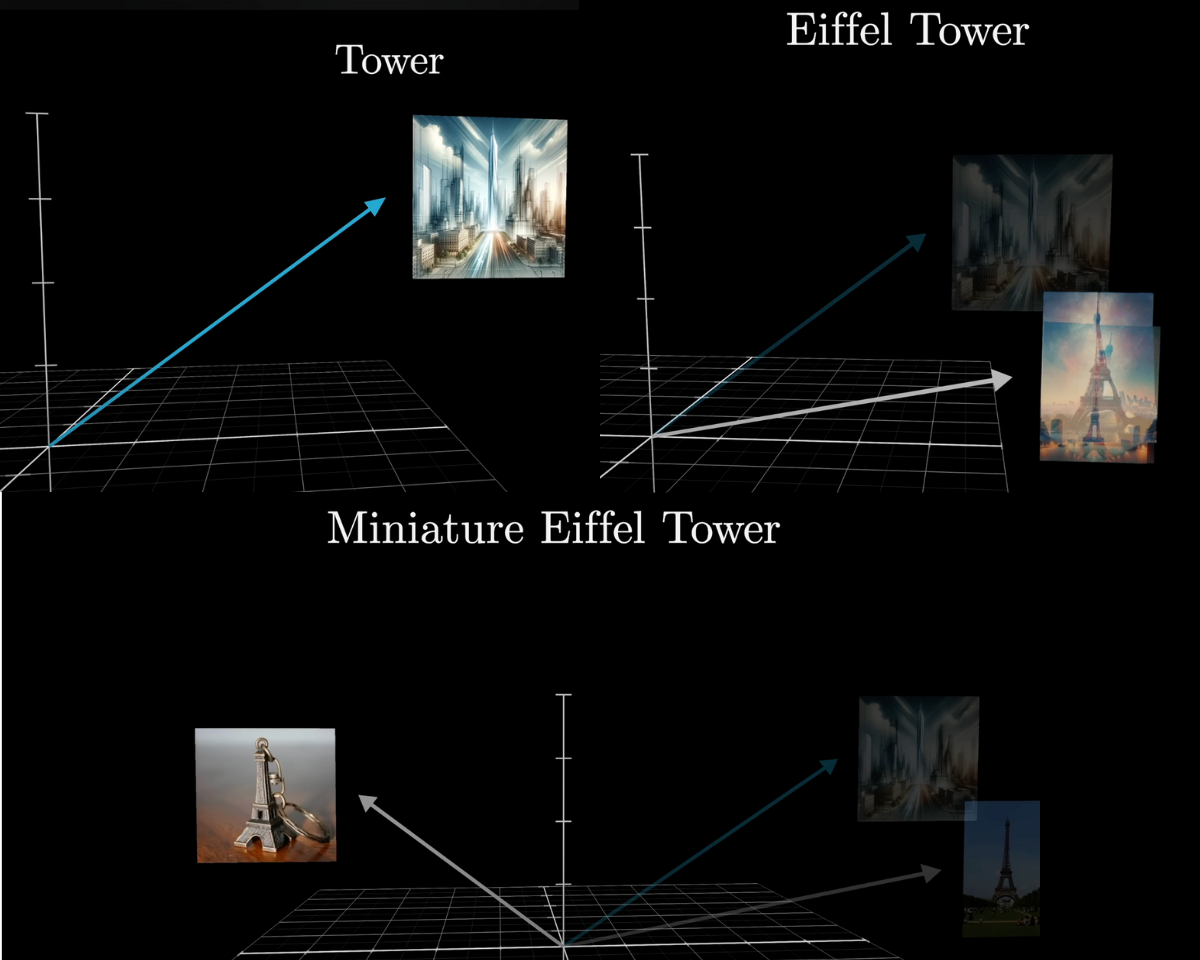

In a similar vein, we create vectors for words. These vectors are typically enormous, for example one of the LLAMA models uses a 4096-dimensional vector for each word in its vocabulary (the vocabulary of an LLM, much like that of a person, is the set of all words they know and can work with). The set of all these vectors that can represent words is called the ‘embedding space’.

Each dimension of the vectors in the embedding space captures something different, and these could get quite abstract: tense, noun-ness, archaic-ness, slang-ness, how much this relates to other concepts, etc.

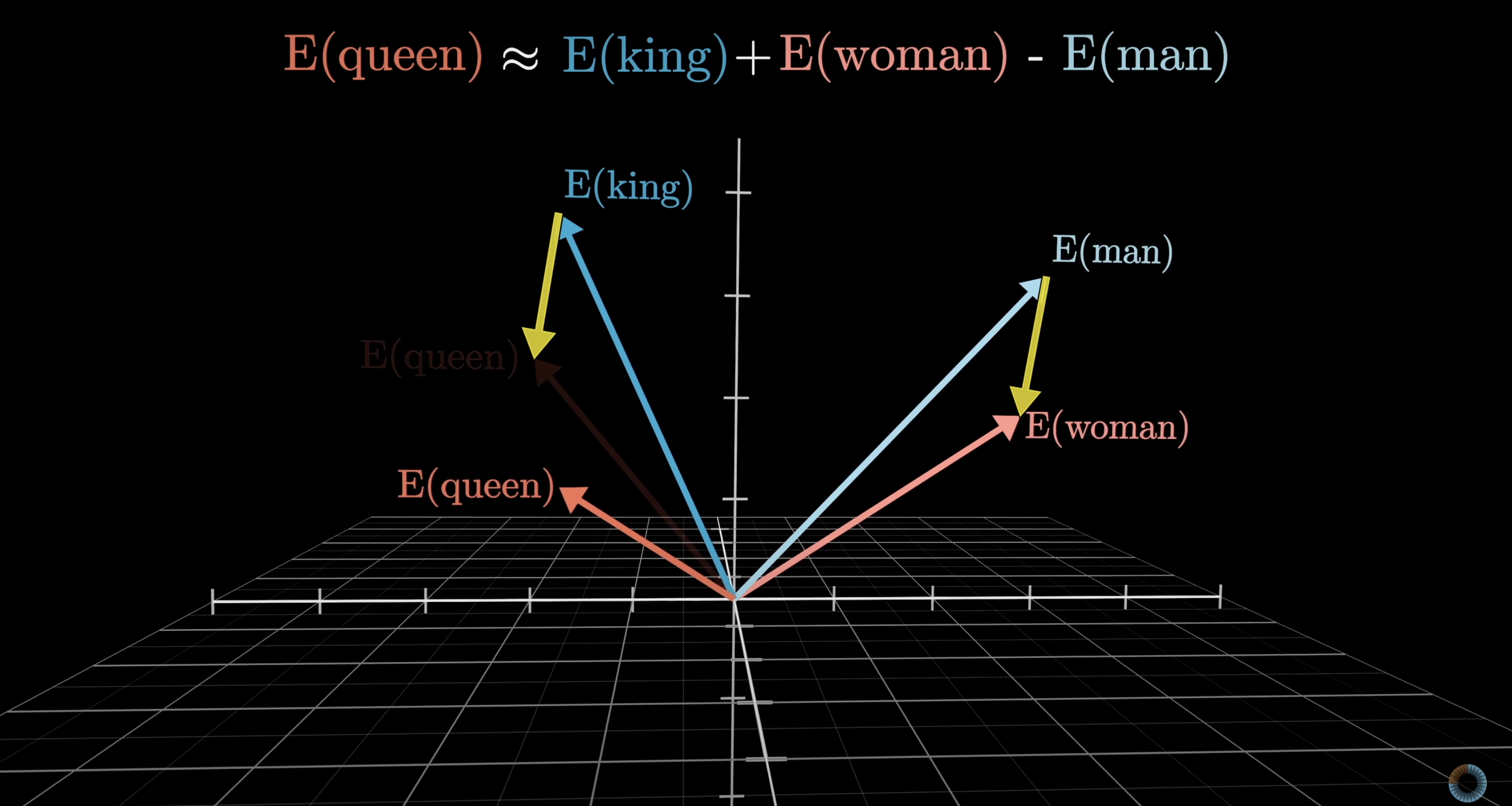

Now we should be able to do math on this. What does this mean? Well, back to our person classification example, if we get the vector representating a tall dark-skinned person, and subtract from that a vector with a high dark value and a high height value, then we should get a vector similar to that of a person who is short and light-skinned.

So, if we have a vector representing “king”. Subtract the vector for “man”. Add the vector for “woman”. This should be close to … the vector for “queen”.

Every vector must, however, be associated with a real word - there is a function that maps words to the embedding space and back. So if we end up with a new vector, the function must somehow map it back to a known existing word. The group of words we can use is called the “vocabulary” (funny, that). We can have a very large expressive vocabulary, but this requires more compute. Or, we could have a smaller vocabulary and be faster at computing answers, but be able to say less.

Summary and terms

To reiterate, LLMs use a database, called a vocabulary, of words, called tokens, where each word maps to a large vector of numbers, called embedding vectors. These embedding vectors represent with many dimensions all the different concepts, relationships, and semantic meaning a token might hold.

Now that we’ve seen how words become numbers, let’s explore how Transformers use those numbers to predict text

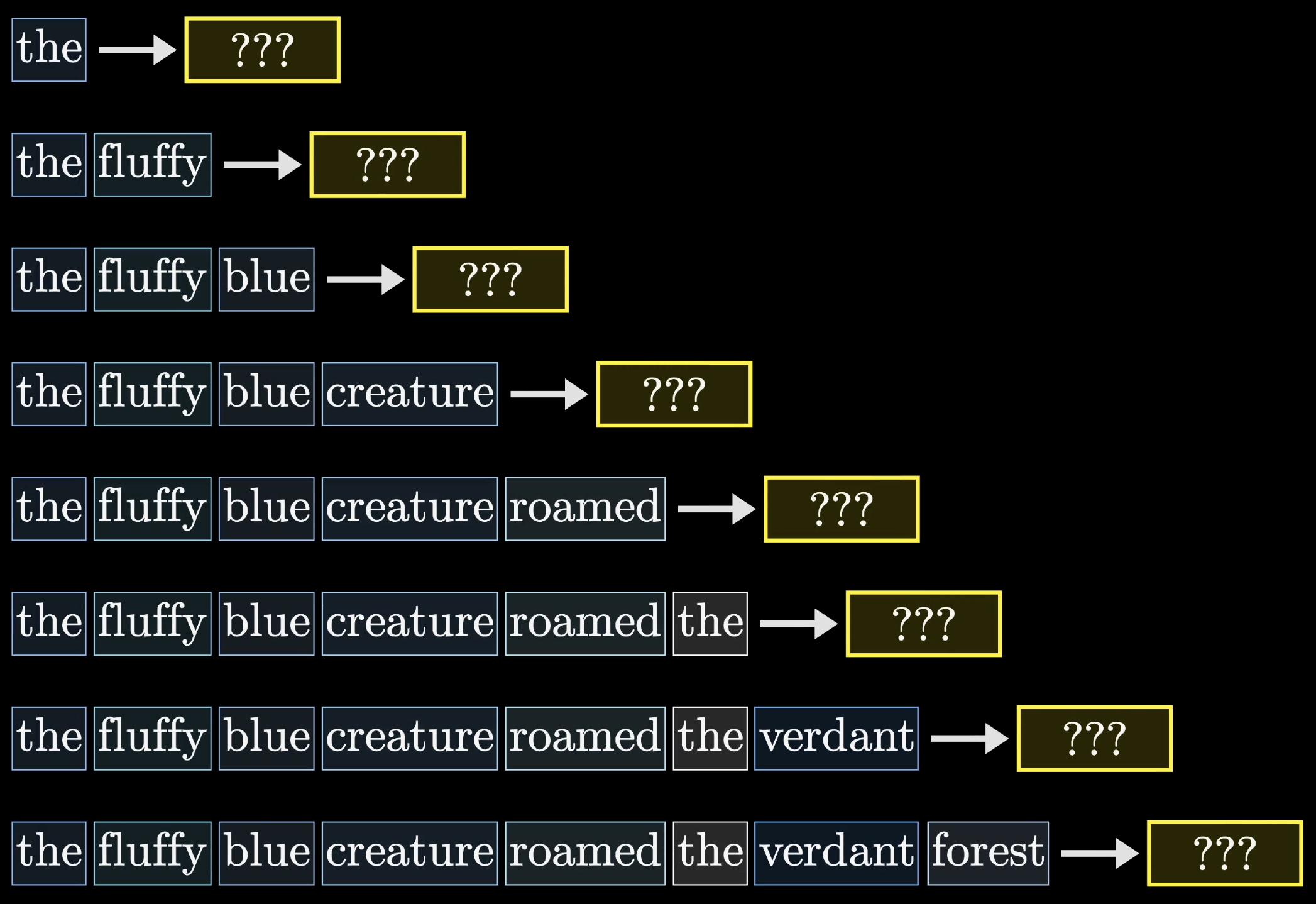

Transformers

So we have the embedding space. Instead of words, we work on large vectors which encapsulate a lot of concepts and “type-ness” about each word. Let’s focus on the core use case of a LLM: we have some text, what comes next in that text? (note: transformers can do other things, but I’m going to focus on a use case initially to make the explanation easier) This is where a transformer can help. A standard-configuration for a transformer will take as input a series of vectors - representing tokens, or words - and by checking all these against each other, figure out which vector in embedding space - so which word in the vocabulary - is the most likely to come next. This can be generalised, of course, to any embedding space. Maybe the embedding space was trained on more abstract concepts than words. The transformer is merely trying to say “given these vectors, which one is the mostly likely to come next”.

So how does it do that? With a mechanism called Masked Self-Attention (again, this can be abstracted and there are more types of attention, like cross-attention. I focus on one example to get the point across).

Masked:

This Masked Self-Attention takes in a certain-sized “context window”, which is the number of vectors it can consider at once. Maybe it deals with fewer, to start. If the context window is 8, and it starts with 1 vector, then we have 7 empty positions - and it’s trying to predict position 2. This is where the “Masked” part is relevant. This type of Transformer uses causal relationships, so it only looks at past vectors (words) to predict the rest. Imagine your friend writes part of a sentence, and you have to give the next word. You can only use what they have written so far, not anything they “might write in the future”, to guess that word. Eg. They write “the quick brown fox ___”. What’s next? Unmasked attention is not causal, and uses the whole window. This is less for “predicting the next vector (word)” and more for “understanding a whole concept”. So part of ChatGPT uses this wholistic Self-Attention, on the input prompt, to understand everything at once. Why is this necessary? Because the later parts of a sentence, or a paragraph, influence understanding of the earlier parts, and vice versa. “It was lucky that Sara had an umbrella” - if we just consider this unidirectionally, it can be hard to understand what “it” is and why that might be lucky. Bidirectionally, we can see that the umbrella is relevant to the luck.

But when predicting, we cannot use that which hasn’t been predicted yet. Therefore: the mask. This blocks all future vector (word) positions from the Attention so that we only look at the past vectors. This might sound silly when generating new text, but is particularly important when training - this is when it actually does have access to the future data, but we don’t want it to learn that.

The following image demonstrates how the transformer sees phrases - when predicting each future word, it can only look at past words:

Self:

This means that the Transformer looks at what the context window - both what it got given and what it generated - and compares to its own embedding space. It could compare to different spaces (we’ll get there), but in this example, it’s contained. Only the input data and generated data and how it relates to itself is relevant

Attention:

Ok, now we have the context (ha), let’s go over the core part. This is excellently explained in 3Blue1Brown, with nice diagrams, so if you want more technical detail I recommend checking that out.

It’s not looking at the future, it’s checking only with itself … but what is it doing? So for each input vector (word) we want to check it against every other input vector. We want to know how relevant everything is to everything else, and if it is relevant, what does that mean for the future of this vector set (sentence). How do we do that? For each embedding vector, we get three things: a query, a key, and a value. These are each vectors, attained by weighted multiplication, but I’m going to refer to them by the names to keep things clear. The query says “what information does this vector want?”. For example, a verb - ‘walk’, say - wants a tense (past, present, etc). The key says “what information does this vector contain?”. A verb contains, well, an action. This could be relevant to a subject, which might want an action. Eg. “You”, as a vector, might want an action to be doing in this sentence and the “walk” vector contains said action. The value will make more sense in its place, so let’s discuss how the query and the key are used.

Queries and Keys

So one of the major powers of attention is that everything in the sentence so far asks everything else “what are you doing here” (in a roundabout way). In “The cat sat on the mat. It was”, we have cat checking in with ‘sat’, ‘mat’, ‘on’, ‘it’. And mat checks in with all those things, and so does sat, etc. Is “it” mat, is “it” cat … how else would we know, but to compare it to all those things. So each vector’s (word’s) query is compared with each other vector’s key (including the one querying) for similarity, how close they are. If the query is saying “what am I after” and the key is saying “what can I offer”, and these are similar - this is useful! One vector is looking for something tense-like, and another vector might contain a tense that helps!

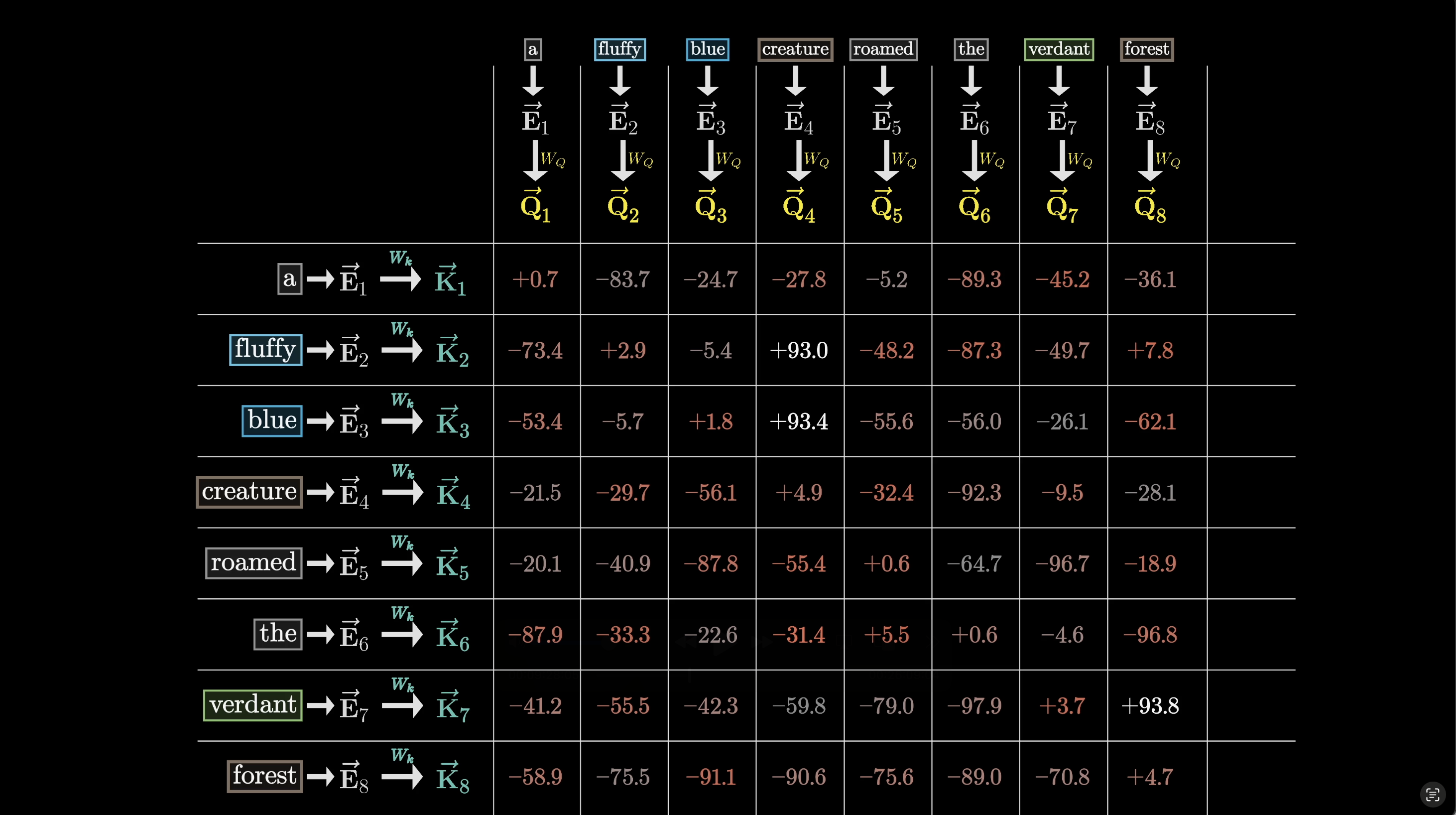

Here’s a numerical example, from 3Blue1Brown:

In the above image, we can see the numerical result from each Query-Key computation, for each pair of words/tokens.

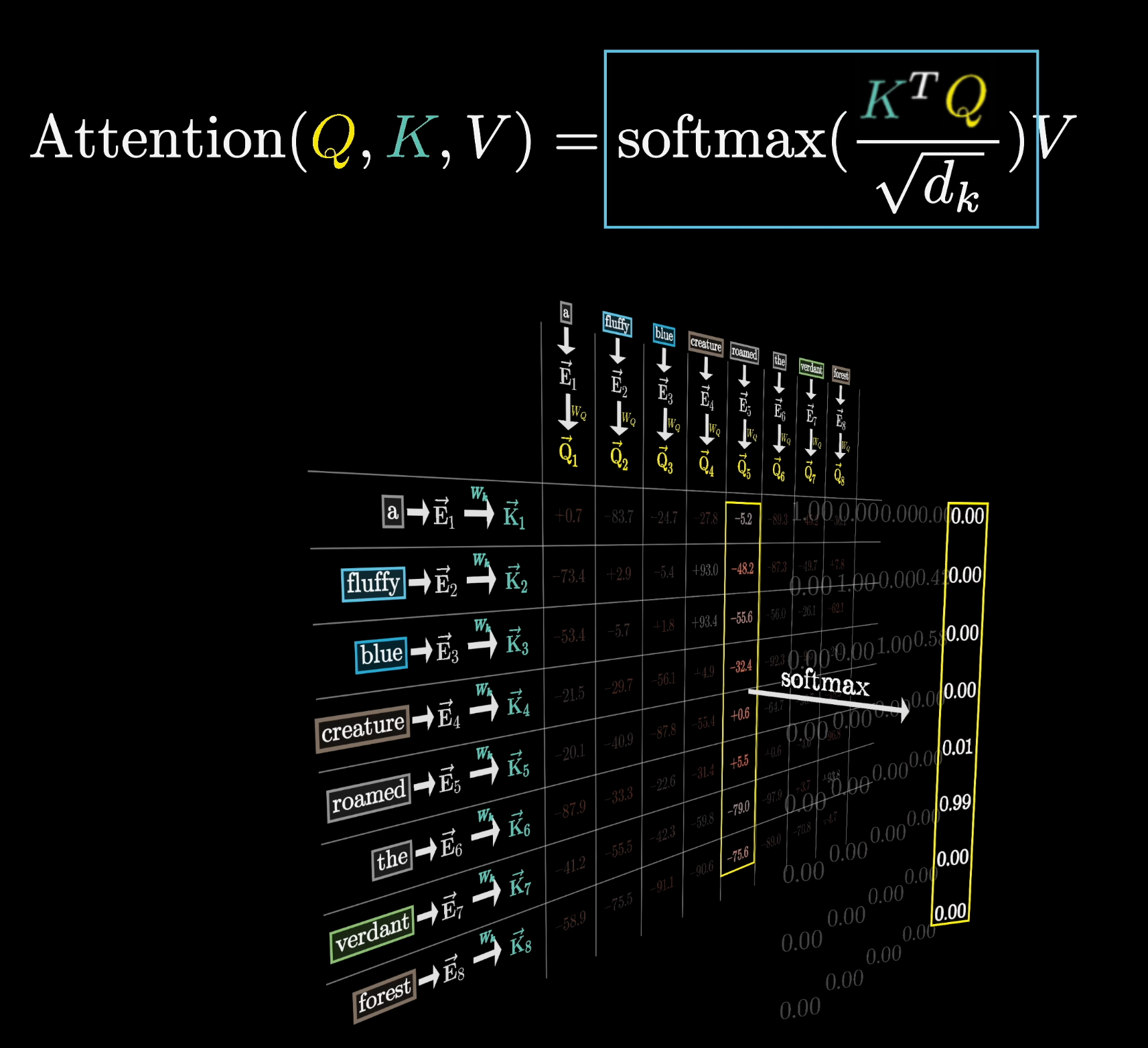

What next?

This similarity is converted to a probability (so, ranging from 0-1), and multiplied with the values for each vector. The value for a vector is “What information will I provide?”. So if something is asking for a tense, something else says “I can offer a tense”, then what tense will it provide? The value answers this. It might be “present tense”, for example, “ing” makes “walk” into “walking”, present tense. Or “ed”, to make it past tense. This is a simple example, but hopefully gets the point across. Another example is “pet” could be looking for an animal type, another vector “cat” could offer an animal type and provides “siamese”.

Here’s 3Blue1Brown again, showing the probabilistic result:

These probabilities will weight different dimensions in the value, which is then converted back to embedding space. For the “pet” example, there might also be a dimension of “nationality”, and this would get given a very low probability (multiplied with a number close to 0), and therefore have very little effect; the “breed” dimension might get weighted higher, have a number close to one. This would then give a higher value in embedding space.

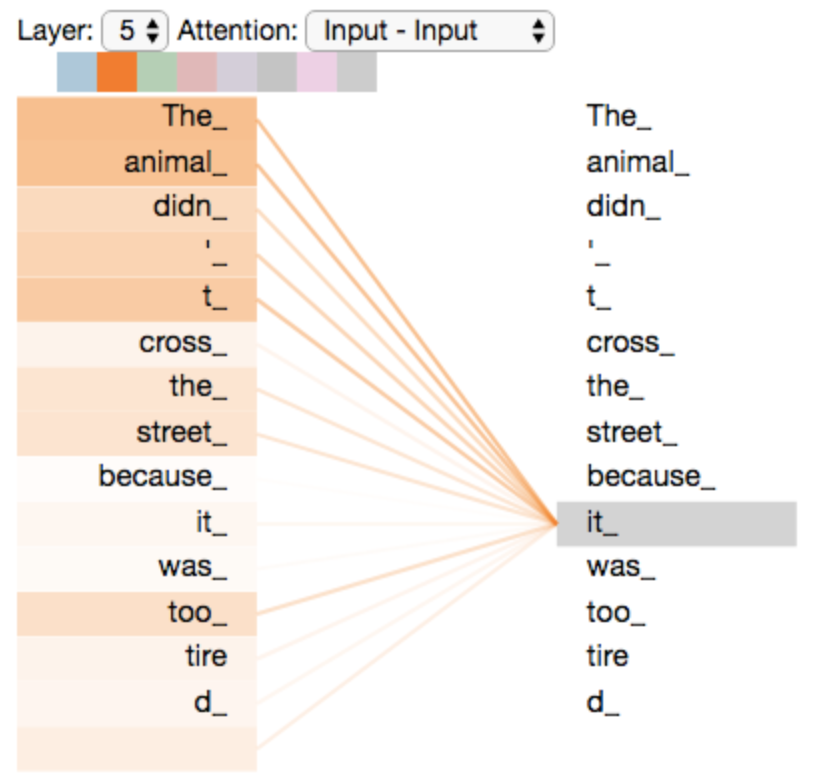

Here’s a visual example, from Jay Alammar’s blog.

The above image displays the attention of ‘it’ across the entire input vector. Colour intensity represents higher probabilities, so we can see that ‘it’ relates very strongly to ‘The animal’ (as expected), but also, less probably, to ‘street’. The latter is possible; consider “The animal didn’t cross the street because it was too dangerous” - here, ‘it’ refers to the street.

Result

The result of all of this is a new embedding vector. Let’s just summarise the journey of our embedded vector through attention. We have some embedding vectors from an input prompt sentence (this could be the previous output). Each word multiplies its query with every word’s key, to see how similar they are. These are converted to probabilities, so the most similar dimensions become really high probabilities and so on. These are then multiplied with each vector’s value, to get the most likely information passed on from that vector. Then, this gets added back onto the original embedding vectors. Why? To “tweak” it in embedding space. A vector might start out representing a simple concept, “walk”. The attention head notices that the sentence has high attention to tense, and current time, therefore the value vectors give us “ing”, and this gets added back onto the vector to shift the vector towards the concept of present tense walk.

Finally, this gets converted back from embedding space to vocabulary space, with probabilities. That is, we have a giant dictionary that is our vocabulary, where words are ordered: word #1, word #2, and so on. In each position, 1, 2, etc, this conversion gives us a probability that the vector from embedding space was converted to this word. “Walking” might be the highest probability, but “walked” may not be that far behind. “Antitrust” would get a very low probability in this case, as its entirely unrelated. The highest probability word is chosen as the next word then, and written out. The following figure shows this process, bottom up. We take the output vector, and pass it through a linear operation to get logits - these are log-likelihoods for each index. The softmax operation converts real-numbered values - the log-likelihoods, which range from negative infinity to positive infinity - to proportionate numbers between 0 and 1. That is, probabilities. Then we get the highest probaility value, and find the word that corresponds to.

To continue generating the sequence, the new word is appended to what has been written so far, and passed back in to start the whole process again.

Summary

So going over attention again: for the initial prompt, we take each word - as a vector - and get three things: tis query, its key, its value. Then we compare each word’s query to every other word’s key, seeing how similar “what do I want” and “what do I contain” for each pair of words are. The amount of similar then scales the value, which is “what can I offer”. Finally, this gives a set of probabilities over the whole vocabulary, which allows us to check what the most likely next word is. Then this next word is fed back in, we get queries, compare to each key, scale a new value, and so on. For a better-written, more visually explained, although also more technical, explanation, see Jay Alammar’s blog.

Wrapping up

This should give you a good idea of what’s happening next time you ask ChatGPT a question - it has processed how each word in your prompt relates to every word - or rather, token - in its vocabulary, which is vast indeed. Then it figures out the most likely token that comes next … and repeat. If you ask “Explain thermodynamics”, then the likely tokens are ones that relate to heat, entropy, and various laws. But it does better than just that, It won’t just say “heat law thermo”, since the most likely token after “law” is “of”, and so on.

Another example: when you ask for a summary of text, the embedding vectors that get created attempt to contain all the relationships and meaning in the original text, but in a dense form. Then when they are converted from vectors into tokens, the tokens are “This detaisl the second law of thermodynamics” rather than an entire paragraph to say the same.

Of course, the actual process involves a whole lot more. You can have multiple attention layers, each tweaking the embedding vectors and the concepts they represent slightly. Each attention layer is trained to focus on different ideas, and so on. But this should hopefully be a good broad overview to help understand the base functionality.